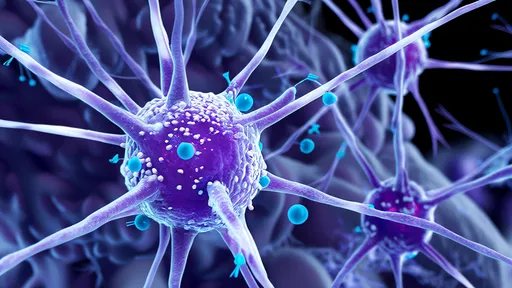

The human brain is a remarkably adaptable organ, capable of rewiring itself in response to repeated experiences and behaviors. This phenomenon, known as neuroplasticity, forms the biological foundation for habit formation. When we consistently engage in a particular activity or thought pattern, our neural pathways undergo physical changes to make that behavior more automatic and efficient. Understanding this process provides profound insights into how habits—both beneficial and detrimental—take root in our lives.

At the core of habit formation lies the strengthening of synaptic connections between neurons. Each time we repeat an action, the associated neural circuit becomes more robust through a process called long-term potentiation. This electrochemical reinforcement makes the pathway more sensitive and likely to fire in the future. What begins as a conscious effort gradually transitions into automatic processing as the brain creates neural shortcuts. The basal ganglia, a deep brain structure, plays a particularly crucial role in this transition from deliberate action to habitual behavior.

Neurotransmitters act as chemical messengers in this process, with dopamine serving as a key player in habit reinforcement. When a behavior produces a rewarding outcome, dopamine release strengthens the connection between the cue and the response. This creates a feedback loop that makes us more likely to repeat the behavior under similar circumstances. Over time, the anticipation of reward alone can trigger the habitual response, explaining why habits often persist even when the original reward is no longer present.

The brain's remarkable efficiency comes at a cost—it tends to prioritize well-worn neural pathways over creating new ones. This explains why breaking established habits feels so challenging. The existing circuitry has become the path of least resistance, requiring conscious effort to override. However, the same neuroplasticity that created the habit can be harnessed to change it. By consistently practicing new behaviors, we can gradually weaken old pathways while strengthening new ones.

Sleep emerges as a crucial factor in habit formation that many overlook. During sleep, particularly during REM cycles, the brain consolidates and reinforces the neural patterns formed during waking hours. This means that quality sleep enhances our ability to develop new habits while making existing ones more entrenched. Chronic sleep deprivation, conversely, can disrupt this process and make behavioral changes more difficult to sustain.

Environmental cues exert powerful influence on our habitual behaviors through conditioned neural responses. The brain associates specific contexts—whether physical locations, times of day, or emotional states—with particular routines. These associations become so strong that encountering the cue automatically activates the habitual response, often without conscious awareness. This explains why changing environments can be an effective strategy for breaking unwanted habits and establishing new ones.

Contrary to popular belief, habit formation isn't simply a matter of repeating an action for 21 days. The timeline varies significantly depending on the complexity of the behavior, individual differences in neurochemistry, and the consistency of practice. Some simple habits may form relatively quickly, while complex behaviors might require months of repetition before becoming automatic. The key lies in the quality and context of repetition rather than adhering to an arbitrary timeline.

Stress and emotional states significantly impact the habit formation process. During periods of stress, the brain tends to default to established patterns rather than expending energy on new behaviors. This explains why people often revert to old habits during challenging times, even after making progress with new routines. Understanding this tendency can help individuals develop strategies to maintain behavioral changes during stressful periods.

The interplay between conscious decision-making and automatic processing reveals an important insight about habit change. While willpower plays a role in establishing new patterns, relying solely on conscious control is ultimately unsustainable. The true power lies in shaping our environments and routines to make desired behaviors easier to perform automatically. This approach aligns with how our brains naturally function, working with our neurobiology rather than against it.

Recent advances in neuroimaging have allowed scientists to observe habit formation in real time. Functional MRI studies show how activity shifts from the prefrontal cortex (associated with conscious decision-making) to the basal ganglia (associated with automatic behaviors) as a habit becomes established. These findings confirm that habit formation isn't about eliminating thought, but rather about transferring the processing to different brain regions.

The implications of habit-related neuroplasticity extend far beyond personal development. Understanding these mechanisms can inform more effective educational strategies, addiction treatment programs, and rehabilitation approaches. By working with the brain's natural learning processes, interventions can be designed to create lasting behavioral change. This knowledge also helps explain why some therapeutic approaches succeed where others fail, based on how they engage the brain's plasticity mechanisms.

Age-related differences in neuroplasticity suggest that habit formation strategies might need to vary across the lifespan. While younger brains generally demonstrate greater plasticity, older brains retain significant capacity for change. The key difference lies in the pace and approach—older individuals may require more repetition and stronger contextual cues to establish new patterns, but the fundamental mechanisms remain intact throughout life.

Practical applications of this knowledge abound. By understanding that habits form through cue-routine-reward loops, individuals can deliberately design new patterns. Keeping the cue and reward constant while gradually modifying the routine proves more effective than attempting radical changes. This approach respects the brain's existing wiring while gently steering it toward healthier patterns.

The relationship between habit formation and identity reveals a deeper layer of neuroplasticity. As behaviors become habitual, they begin to shape our self-perception at a neural level. Repeated actions literally rewire the brain to incorporate them into our self-concept. This explains why lasting change often requires adopting new identities rather than just implementing new behaviors—the brain ultimately aligns its wiring with how we consistently see ourselves.

Emerging research suggests that certain pharmacological agents might enhance neuroplasticity and potentially accelerate habit formation. However, the ethical implications and long-term effects of such interventions remain unclear. More promising are non-invasive techniques like neurofeedback and targeted cognitive exercises that may help optimize the brain's natural plasticity for habit change without artificial enhancement.

Ultimately, the neuroscience of habit formation offers both explanation and empowerment. While our brains are wired to create efficient routines, we retain the ability to consciously shape which routines become automatic. This understanding removes moral judgment from habit formation, framing it instead as a neurological process that can be understood and guided. With patience and strategic practice, we can harness our brain's plasticity to cultivate habits that serve our wellbeing and goals.

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025