The human capacity to endure pain is not solely determined by physiological factors but is profoundly influenced by psychological conditioning. While most people view pain as an unavoidable physical sensation, emerging research reveals that mental training techniques can significantly alter one's perception of discomfort. This discovery has far-reaching implications, from athletic performance to chronic pain management, challenging conventional approaches to pain tolerance.

At the core of psychological pain tolerance lies the concept of cognitive reappraisal. Rather than viewing pain as a threat, individuals can learn to reinterpret it as a neutral signal or even a positive indicator of growth. This mental shift doesn't eliminate the physical sensation but changes its emotional impact, making it more manageable. Marathon runners, for instance, often describe hitting "the wall" not as a reason to stop but as a milestone in their journey.

The power of attention regulation plays a crucial role in pain management. By consciously directing focus away from the pain sensation and toward a specific task or external stimulus, individuals can effectively reduce their subjective experience of discomfort. This technique explains why soldiers in combat sometimes don't notice severe injuries until the battle concludes - their focus remains entirely on survival rather than on their bodily sensations.

Visualization techniques have shown remarkable effectiveness in clinical settings. Patients undergoing painful procedures who imagine themselves in peaceful environments or visualize their pain as a controllable object consistently report lower pain levels. This method works by activating the same neural pathways that process actual sensory experiences, essentially creating competing signals that dampen pain perception.

Breath control serves as another potent psychological tool for pain tolerance. Specific breathing patterns can activate the parasympathetic nervous system, reducing stress responses that typically amplify pain perception. The connection between rhythmic breathing and pain tolerance has been recognized in various traditions for centuries, from yogic practices to martial arts training.

Language and self-talk significantly influence pain perception. The words we use to describe our pain - whether we frame it as "unbearable" or "manageable" - shape our actual experience. Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques have demonstrated that modifying internal dialogue about pain can lead to measurable changes in pain tolerance thresholds.

The role of expectation and conditioning cannot be overstated in pain tolerance. Placebo studies consistently show that when people believe a treatment will reduce their pain, their brains often produce natural pain-relieving chemicals. This phenomenon highlights how our beliefs and past experiences fundamentally alter our neurological responses to painful stimuli.

Social and cultural factors contribute substantially to individual differences in pain tolerance. In cultures where endurance is highly valued, individuals often display remarkable capacity to withstand discomfort. This suggests that pain tolerance is not just an individual trait but is shaped by collective beliefs and social reinforcement.

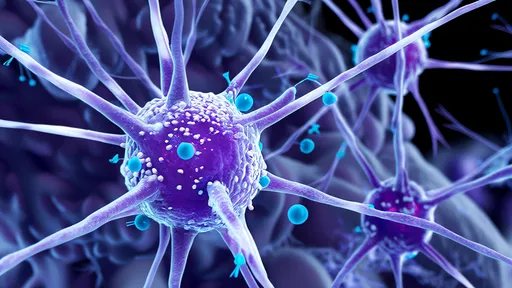

Recent neuroscience research reveals that experienced meditators show different brain activity patterns when exposed to pain compared to non-meditators. Their brains process the sensory information but generate less emotional reaction to it. This finding supports the idea that regular mental training can physically alter how the brain processes pain signals over time.

The relationship between stress and pain creates a vicious cycle that psychological approaches aim to break. Chronic stress lowers pain thresholds, making individuals more sensitive to discomfort, while persistent pain increases stress levels. Mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques have proven particularly effective in interrupting this cycle by cultivating non-reactive awareness.

Environmental context dramatically affects pain perception. The same physical sensation may feel more intense in a frightening or unfamiliar setting compared to a safe, controlled environment. This explains why creating calming surroundings during medical procedures can significantly improve patient comfort without pharmaceutical intervention.

Personality traits interact with pain tolerance in complex ways. While some characteristics like neuroticism may predispose individuals to greater pain sensitivity, these tendencies are not fixed. Targeted psychological training can help individuals develop coping strategies that work with their natural inclinations rather than against them.

The duration of pain significantly impacts how individuals cope with it. Acute pain often triggers fight-or-flight responses, while chronic pain requires different psychological strategies focused on acceptance and long-term adaptation. This distinction explains why pain management approaches must be tailored to the specific temporal nature of the discomfort.

Emotional states serve as powerful modulators of pain perception. Depression and anxiety typically lower pain thresholds, while positive emotions can provide natural analgesia. This connection forms the basis for therapeutic approaches that address emotional wellbeing as part of comprehensive pain management programs.

Practical applications of psychological pain tolerance training are expanding rapidly. From military programs preparing personnel for potential injuries to childbirth education classes teaching pain management techniques, these methods are proving their worth across diverse fields. The common thread is recognizing pain as an experience that can be shaped rather than merely endured.

Future research directions point toward personalized pain tolerance training based on individual neurological profiles. As brain imaging technology advances, we may develop the ability to identify which psychological techniques will work best for specific individuals, revolutionizing how we approach pain management in clinical and everyday settings.

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025